“As the acronym shifts daily, we don’t know if these videos are actually being produced by a ragtag force seeking to provoke a superpower and her allies into war or if Isis is rather a front for more institutional actors, even states, pretending to be such a grassroots group. This is vital for knowing whether this development is one toward or away from the democratisation of the narrative.”

American documentary maker Eugene Jarecki

While some have attempted to distinguish between the disassociated “romantic freedom fighters” and actual terrorist cells, the concern is that these young volunteers, some now radicalized and combat-trained, will wreak havoc and become uncontainable. The driving question here is why, precisely, have these young civilians turned combatants elected in a life of insurgency? Namely, why would anyone with an entire life ahead of them even want to risk their life to fight in someone else’s war?

With a special reference to the factors motivating drivers of violent extremism amongst youth foreign fights, one must take pause to summarize what is it that we actually already know about youth participation in violent extremism in the first place– be it as a foreign combatant recruit or otherwise. Some of the most common misconceptions in the study of youth violent extremists are propagated by misinformed theories supported by inherent limitations, i.e. those which rely heavily on generalist, macro-level “root causes.” Amongst youth scholars and experts one such diminutive general theory of conflict is the “youth in crisis” paradigm whose premise juxtaposes the youth specific opportunities for violence and rebellion with the econometric “greed versus grievance” model of human development and conflict manifestation. In discussing the different factors motivating youth recruitment, this debate attracts attention. While the opportunity structure arguments emphasize the preeminence of rational choice, grievance arguments specify the role of identity, disparity in intergroup relationships, and the effect of unmet basic needs.

However romantic, this argument disregards new empirical knowledge evidencing that the majority of youth affected by the underlying conditions linking them to violent extremism are not clear; few among them are actually motivated primarily by these so called “youth crisis” conditions in question. It is important to note that youth foreign fighter recruitment has manifested itself in a wide variety of socioeconomic settings across both impoverished societies to advanced industrialized countries. Therefore, it is very difficult to generalize about these underlying conditions since violent organizations emerge in radically different social, political, and economic environments. Furthermore, these explanations often framed in terms of causality or “root drivers” disregard the importance of the role of human agency. With a solitary focus on rationalist presumptions and explicit concerns with particular social and economic conditions, the role of essential push factors have been largely overstated. Such assumptions underestimate the potentially critical role played by the important pull factors like the appeal of a particularly inspirational leader or the material, emotional, or spiritual benefits which affiliation with an extremist group may confer to potential youth recruits.

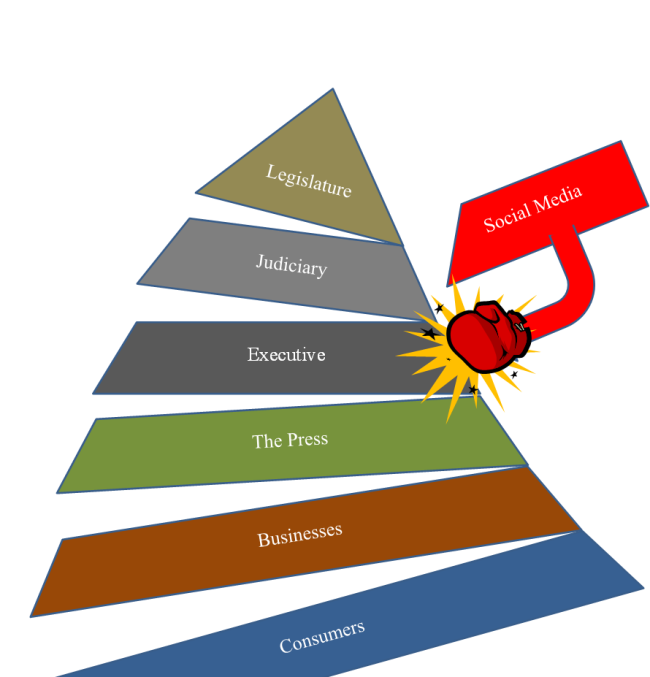

Recent research has begun to look at how parties of conflicts have effectively used social media to increase their visibility, spread their message, and communicate to scale. Noting “Why Terrorists Love Twitter,” Time Magazine addressed ISIS and the challenge social media sites face when violent groups use their platforms in social media to engage and converse amongst themselves as well as to effect change on a global level. In recent years, policymakers, practitioners, and the academic community have begun to examine how the internet influences the process of radicalization extremist activities are recurrent theme to this topic. As a place where individuals find their ideas supported and echoed by other like-minded individuals, it is difficult to argue against the idea that the internet plays an important role in the process of recruiting young violent extremists. Many violent groups see organization on social media as a way to get money from wealthy foreigners sympathetic to a cause. This fits well within the widely utilized tactic of putting a young face at the forefront of campaigns deploying youth to combat zones.

This may be the reason why, in combination with many other strategies, the US State Department headed by the tiny Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC) has ramped up efforts to strategically neutralize jihadist propaganda online as violent militants flood social media. Every attempt from the production of a State Department branded Youtube Channel to a Facebook Group and Twitter account has been generated under the US’s newest approach to use their PR and communication skills as a way to “engage in our very particular brand of adversarial engagement.”

Considering the idea of internet based self-radicalization, at the individual level, evidence does not necessarily support the suggestion that social media and ideological fit can alone accelerate extreme violent action. The spectrum of potential radicalizing factors and the triggers prompting an individual to move from extreme beliefs to violence vary widely. Committing terrorist acts does not necessarily require radical beliefs and extremist beliefs do not lead one directly down the path to terrorism. The confounding of radical beliefs with terrorism remains a highly contested topic exacerbated further by the role of individual and group processes. There remains a significance to localized grievances as well as the need for creating credibility among those who seek either to radicalize or to counter such resistance; group dynamics are a powerful component in pressuring individual action. In regards to the ISIS experience as it relates to youth combatant recruitment, a particular focus on ideology and self-identification highlights the complexity of cause and effect.

Beyond the international coalitions sending troops and conducting airstrikes over Iraq and Syria, perhaps one of the most valuable but unsung approaches thus far has come out of the underfunded State Department CSCC office. Taking it one step farther, and in considering the lack of knowledge in addressing the phenomena at hand, one must look specifically at the constructed perceptions and individual experiences of youth combatants before making any broad assumptions about the trajectories of this situation. With a commitment towards communicating a message for social good, strategic communication here is key to countering the narrative of terrorism. When it comes to new media technology, research shows that access to the internet via social media platforms cannot justifiably replace the need for recruits to meet in person during their radicalization and/or de-radicalization process. However, seeking to account for how young individuals have come to support certain forms of extremism associated with terrorism experts have since argued that the internet may have the ability to enhance and/or catalyze pre-existing opportunities available to young people seeking to become radicalized by providing a greater opportunity than offline interactions to confirm existing beliefs.

Though this does not prove causality for their mobilization in the first place, what is does show is that the internet facilitates the radicalization of individuals, but it is only one part of the whole process. Focusing on the potential interplay between the offline and online worlds of personal history and social relationships, communication across various formal and informal platforms offers a counter narrative supporting opportunities for peaceful coexist.

Right now is our lynchpin moment in terms of positive outreach to young people in the region. Playing upon their identities and experiences, there is opportunity to engage in meaningful dialogue with the young leaders responsible to shape the outcome of this protractedly violent situation, both off and online. The assumption that there is one singular ISIS brand of socio-political religious doctrine which is uniquely extremist will not help us understand the cycles of brutality that have festered for decades. Our approach must acknowledge first through the many means available the circulating narratives and images of torture, violent murder, and desecration. Rather than engaging in useless propaganda banter, and potentially alongside a greater and well planned long term strategic communication strategy, the US and its allies should align not behind their weapons but their words in order to seek out and show solidarity with those young persons resilient enough to risk their lives in the fight for a positive change. With that, perhaps next time it will be to the benefit of social good.

![By H. Murdock, VOA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://theglobalpresent.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/lebanon-syria_border_sep13voa_01.jpg?w=300&h=220)